Lateral epicondylitis (Tennis elbow)

What is lateral epicondylitis?

Lateral epicondylitis is a painful condition affecting the tendons that attach to the outside of the elbow. Although it is commonly known as tennis elbow, is not limited to tennis players. Any activities that repeatedly stress the same forearm muscles can cause symptoms of tennis elbow.

What parts of the elbow are affected?

Tennis elbow causes pain that starts on the outside bump of the elbow, the lateral epicondyle. The forearm muscles that bend the wrist back (the extensors) attach on the lateral epicondyle and are connected by a single tendon. Tendons connect muscles to bone. When muscles work, they pull on one end of the tendon. The other end of the tendon pulls on the bone, causing the bone to move. When you bend your wrist back or grip with your hand, the wrist extensor muscles contract. The contracting muscles pull on the extensor tendon. The forces that pull on these tendons can build when you grip things, hit a tennis ball in a backhand swing in tennis, or do other similar actions.

Tennis elbow causes pain that starts on the outside bump of the elbow, the lateral epicondyle. The forearm muscles that bend the wrist back (the extensors) attach on the lateral epicondyle and are connected by a single tendon. Tendons connect muscles to bone. When muscles work, they pull on one end of the tendon. The other end of the tendon pulls on the bone, causing the bone to move. When you bend your wrist back or grip with your hand, the wrist extensor muscles contract. The contracting muscles pull on the extensor tendon. The forces that pull on these tendons can build when you grip things, hit a tennis ball in a backhand swing in tennis, or do other similar actions.

What causes tennis elbow?

Overuse of the muscles and tendons of the forearm and elbow are the most common reason people develop tennis elbow. Repeating some types of activities over and over again can put too much strain on the elbow tendons. These activities are not necessarily high-level sports competition. Hammering nails, picking up heavy buckets, or pruning shrubs can all cause the pain of tennis elbow.

Overuse of the muscles and tendons of the forearm and elbow are the most common reason people develop tennis elbow. Repeating some types of activities over and over again can put too much strain on the elbow tendons. These activities are not necessarily high-level sports competition. Hammering nails, picking up heavy buckets, or pruning shrubs can all cause the pain of tennis elbow.

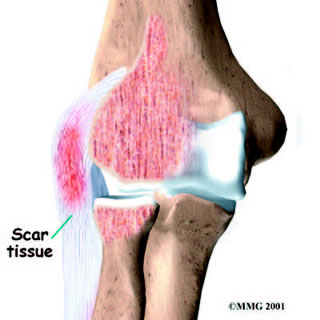

In tennis elbow, the problem is within the cells of the tendon. Wear and tear is thought to lead to tissue degeneration. The tissue that makes up the tendon becomes fragile and can break or be easily injured. The body responds by forming scar tissue in the tendon. Eventually, the tendon becomes thickened from extra scar tissue. No one really knows exactly what causes this. Some doctors think that the forearm tendon develops small tears with too much activity. The tears try to heal, but constant strain and overuse keep re-injuring the tendon. After a while, the tendons stop trying to heal. The scar tissue never has a chance to fully heal, leaving the injured areas weakened and painful.

What are the symptoms?

The main symptom of tennis elbow is tenderness and pain that starts at the lateral epicondyle of the elbow. The pain may spread down the forearm. It may go as far as the back of the middle and ring fingers. The forearm muscles may also feel tight and sore. The pain usually gets worse when you bend your wrist backward, turn your palm upward, or hold something with a stiff wrist or straightened elbow. Grasping items also makes the pain worse. Just reaching into the refrigerator to get a carton of milk can cause pain. Sometimes the elbow feels stiff and won't straighten out completely.

How is it diagnosed?

Your doctor will first take a detailed medical history. You will need to answer questions about your pain, how your pain affects you, your regular activities, and past injuries to your elbow. The physical exam is often most helpful in diagnosing tennis elbow. Your doctor may position your wrist and arm so you feel a stretch on the forearm muscles and tendons. This is usually painful with tennis elbow. There are also other tests for wrist and forearm strength that can be used to detect tennis elbow. You may need to get X-rays of your elbow. The X-rays mostly help your doctor rule out other problems with the elbow joint. The Xray may show if there are calcium deposits on the lateral epicondyle at the connection of the extensor tendon. Tennis elbow symptoms are very similar to a condition called radial tunnel syndrome. This condition is caused by pressure on the radial nerve as it crosses the elbow. If your pain does not respond to treatments for tennis elbow, your doctor may suggest tests to rule out problems with the radial nerve.

When the diagnosis is not clear, your doctor may order other special tests such as an MRI or ultrasound scan.

What is the treatment?

Nonsurgical treatment:

The key to nonsurgical treatment is to stop the tendon from degenerating further and to help the tendon heal. If the problem is caused by acute inflammation, anti-inflammatory medications such as ibuprofen may give you some relief. If inflammation doesn't go away, your doctor may inject the elbow with cortisone. Cortisone is a powerful anti-inflammatory medication. Its benefits are temporary, but they can last for a period of weeks to several months. Your doctor may suggest using ultrasound to guide a needle into the sore area. The ultrasound gives a clear picture of areas in the tendon that contain scar tissue. Poking holes in the tendon breaks up scar tissue and gets the tendon to bleed. Bleeding in the tendon helps stimulate the healing response.

Doctors commonly refer patients with tennis elbow for physiotherapy. At first, your therapist will give you tips on how to rest your elbow and how to do your activities without putting extra strain on your elbow. Your therapist may apply tape to take some of the load off the elbow muscles and tendons. You may need to wear an elbow strap that wraps around the upper forearm in a way that relieves the pressure on the tendon attachment. Because tendinosis is often linked to overuse, your therapist will work with you to reduce repeated strains on your elbow. When symptoms come from a particular sport or work activity, your therapist will observe your style and motion with the activity. You may be given tips about how to perform the movement so the elbow is protected.

Surgical treatment:

Surgical treatment:

Sometimes nonsurgical treatment fails to stop the pain or help patients regain use of the elbow. In these cases, surgery may be necessary.

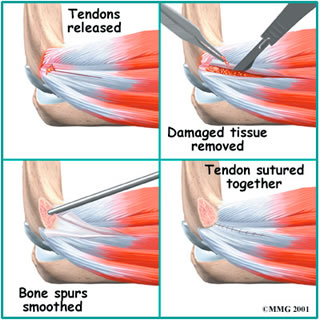

A commonly used surgery for tennis elbow is called a lateral epicondyle release. This surgery takes tension off the extensor tendon. The surgeon begins by making an incision along the arm over the lateral epicondyle. Soft tissues are gently moved aside so the surgeon can see the point where the extensor tendon attaches on the lateral epicondyle. The extensor tendon is then cut where it connects to the lateral epicondyle. The surgeon splits the tendon and takes out any extra scar tissue. Any bone spurs found on the lateral epicondyle are removed. (Bone spurs are pointed bumps that can grow on the surface of the bones.) The skin is then stitched together.