Frozen shoulder / adhesive capsulitis

What is it?

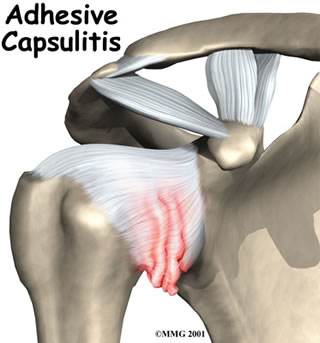

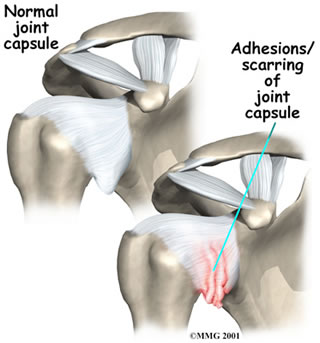

In frozen shoulder, the capsule of the shoulder joint becomes inflamed, thickened and scarred, causing pain and stiffness of the shoulder. It occurs in about 2% of the population, most commonly in those aged 40 to 60 years old, and more often in women than men. The terms frozen shoulder and adhesive capsulitis are often used interchangeably. In other words, the two terms describe the same painful, stiff condition of the shoulder.

What part of the shoulder is affected?

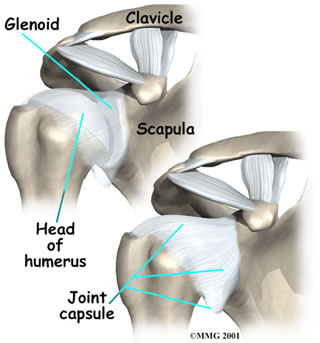

The shoulder is made up of three bones: the scapula (shoulder blade), the humerus (upper arm bone), and the clavicle (collarbone). The joint capsule is a watertight sac that encloses the joint and the fluids that bathe and lubricate it. The walls of the joint capsule are made up of ligaments. Ligaments are soft connective tissues that attach bones to bones. The joint capsule has a considerable amount of slack, loose tissue, so the shoulder is unrestricted as it moves through its large range of motion. As the name suggests, adhesive capsulitis affects the fibrous ligaments that surround the shoulder forming the capsule. This seriously limits the shoulder's ability to move, and causes the shoulder to freeze.

What causes it?

The causes of frozen shoulder are not fully understood. Sometimes an injury or accident may precipitate it, or it may develop after surgery, but often to particular reason for it can be found. It occurs much more commonly in diabetics or those with thyroid problems but it is not known why.

What are the symptoms?

There are usually three phases of a frozen shoulder:

Freezing: there is a gradual onset of pain that becomes progressively worse. The pain is usually aching in nature and felt over the back and outer shoulder area and down the arm. Trying to move the shoulder aggravates the pain. The pain can be extremely severe and cause sleepless nights. The shoulder also gradually gets very stiff and loses most of its range of motion. This phase typically lasts for between 6 weeks to several months.

Frozen: during this phase the pain itself may get better but the stiffness remains. This phase typically lasts for approximately 6 months.

Thawing: the stiffness slowly improves. Complete recovery back to normal, or near normal, strength and range of motion takes up to 2 years.

What is the treatment?

Although frozen shoulder usually gets better by itself over the course of 3 years, the symptoms are often severe enough to require treatment. The main aim of treatment is to relieve the pain and maintain and restore the range of motion.

Non-surgical treatment:

Treatment of adhesive capsulitis can be frustrating and slow. Most cases eventually improve, but the process may take months. The goal of your initial treatment is to decrease inflammation and increase the range of motion of the shoulder. Your doctor will probably recommend anti-inflammatory medications, such as aspirin and ibuprofen.

During the early stage, your doctor may also recommend an injection of cortisone and a long-acting anesthetic, similar to lidocaine, to get the inflammation under control. Cortisone is a steroid that is very effective at reducing inflammation. Controlling the inflammation relieves some pain and allows the stretching program to be more effective.

Physiotherapy can be helpful in maintaining the range of motion and is often a critical part of helping you regain the motion and function of your shoulder. You will often be given exercises and stretches to do as part of a home program. However, overly enthusiastic stretches or manipulations can sometimes make things worse rather than better.

Surgical treatment:

Manipulation Under Anesthesia: If progress in rehabilitation is slow, your doctor may recommend manipulation under anesthesia. This means you are put to sleep with general anesthesia. Then the surgeon aggressively stretches your shoulder joint. The heavy action of the manipulation stretches the shoulder joint capsule and breaks up the scar tissue. In most cases, the manipulation improves motion in the joint faster than allowing nature to take its course. You may need this procedure more than once. This procedure has risks. There is a very slight chance the stretching can injure the nerves of the brachial plexus, the network of nerves running to your arm. And there is a risk of fracturing the humerus (the bone of the upper arm), especially in people who have osteoporosis (fragile bones).

Arthroscopic Release: When it becomes clear that non-surgical treatment has failed, arthroscopic release may be needed. This procedure done under general anaesthetic, together with a nerve block to deaden the arm. The surgeon uses an arthroscope to see inside the shoulder. An arthroscope is a slender tube with a camera attached. It allows the surgeon to see inside the joint. During the arthroscopic procedure, the surgeon can accurately cut and remove the diseased tissue and restore a full range of motion.