Proximal biceps tendon rupture

What is it?

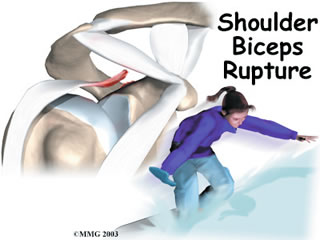

A proximal biceps tendon rupture involves a complete tear of one of the two tendons that attaches the top of the biceps muscle to the shoulder. It happens most often in middle-aged people and is usually due to years of wear and tear on the shoulder. A torn biceps in younger athletes sometimes occurs during weightlifting or from actions that cause a sudden load on the arm, such as hard fall with the arm outstretched.

What parts of the shoulder are affected?

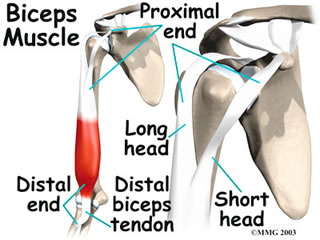

The biceps muscle goes from the shoulder to the elbow on the front of the upper arm. Two separate tendons (tendons attach muscles to bones) connect the upper part of the biceps muscle to the shoulder. The upper two tendons of the biceps are called the proximal biceps tendons, because they are closer to the top of the arm. The long head of the biceps connects the biceps muscle to the top of the shoulder socket, the glenoid. The short head of the biceps connects on the corocoid process of the scapula. The corocoid process is a small bony knob just in from the front of the shoulder. The lower biceps tendon is called the distal biceps tendon. The word distal means the tendon is further down the arm. The lower part of the biceps muscle connects to the elbow by this tendon.

The biceps muscle goes from the shoulder to the elbow on the front of the upper arm. Two separate tendons (tendons attach muscles to bones) connect the upper part of the biceps muscle to the shoulder. The upper two tendons of the biceps are called the proximal biceps tendons, because they are closer to the top of the arm. The long head of the biceps connects the biceps muscle to the top of the shoulder socket, the glenoid. The short head of the biceps connects on the corocoid process of the scapula. The corocoid process is a small bony knob just in from the front of the shoulder. The lower biceps tendon is called the distal biceps tendon. The word distal means the tendon is further down the arm. The lower part of the biceps muscle connects to the elbow by this tendon.

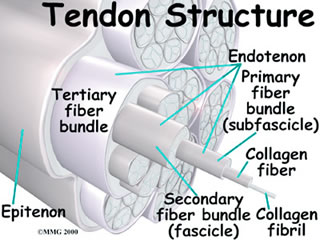

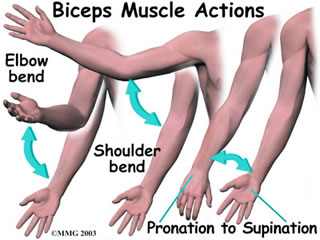

Tendons are made up of strands of a material called collagen. The collagen strands are lined up in bundles next to each other. Because the collagen strands in tendons are lined up, tendons have high tensile strength. This means they can withstand high forces that pull on both ends of the tendon. When muscles work, they pull on one end of the tendon. The other end of the tendon pulls on the bone, causing the bone to move. Contracting the biceps muscle can bend the elbow upward. The biceps can also help flex the shoulder, lifting the arm up, a movement called flexion. And the muscle can rotate, or twist, the forearm in a way that points the palm of the hand up. This movement is called supination, which positions the hand as if you were holding a tray.

Why did my biceps rupture?

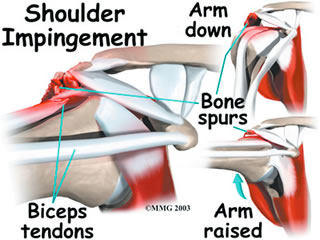

Biceps ruptures generally occur in people who are between 40 and 60 years old. People in this age group who've had shoulder problems for a long time are at most risk. Often the biceps ruptures after a long history of shoulder pain from tendonitis (inflammation of the tendon) or problems with shoulder impingement. Shoulder impingement is a condition where the soft tissues between the ball of the upper arm and the top of the shoulder blade (acromion) get squeezed with arm motion. Years of shoulder wear and tear begin to fray the biceps tendon. Eventually, the long head of the biceps weakens and becomes prone to tears or ruptures. Examination of the tissues within most torn or ruptured biceps tendons commonly shows signs of degeneration. Degeneration in a tendon causes a loss of the normal arrangement of the collagen fibers that join together to form the tendon.

A rupture of the biceps tendon can happen from a seemingly minor injury. When it happens for no apparent reason, the rupture is called nontraumatic. Aging adults with rotator cuff tears also commonly have a biceps tendon rupture. When the rotator cuff is torn, the ball of the humerus is free to move too far up and forward in the shoulder socket and can impact the biceps tendon. The damage may begin to weaken the biceps tendon and cause it to eventually rupture.

What are the symptoms?

Patients often recall hearing and feeling a snap in the top of the shoulder. Immediate and sharp pain follow. The pain often subsides quickly with a complete rupture because tension is immediately taken off the pain sensors in the tendon. Soon afterward, bruising may develop in the middle of the upper arm and spread down to the elbow. The biceps may appear to have balled up, especially in younger patients who've had a traumatic biceps rupture. The arm may feel weak at first with attempts to bend the elbow or lift the shoulder. The biceps tendon sometimes only tears part of the way. If so, a pop may not be felt or heard. Instead, the front of the shoulder may simply be painful, and the arm may feel weak with the same arm movements that are affected with a complete biceps rupture.

How is it diagnosed?

Your doctor will first take a detailed medical history. You will need to answer questions about your shoulder, if you feel pain or weakness, and how this is affecting your regular activities. You'll also be asked about past shoulder pain or injuries. The physical exam is often most helpful in diagnosing a rupture of the biceps tendon. Your doctor may position your arm to see which movements are painful or weak. By feeling the area of the muscle and tendon, the doctor can often tell if the tendon has ruptured. The muscle may look and feel balled up in the middle of the arm, and a dent can sometimes be felt near the top of the shoulder. X-rays may be ordered. X-rays show the bones that form the shoulder joint and may show bony changes that have contributed to a ruptured biceps. Your doctor may also order an ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan.

What is the treatment?

Nonsurgical Treatment:

Doctors usually treat a ruptured long head of biceps tendon without surgery. Not having surgery results in a rarely noticeable loss of strength. Supination (the motion of twisting the forearm such as when you use a screwdriver) is usually affected most. Not repairing a ruptured biceps only reduces supination strength by about 20 percent.

Nonsurgical measures could include a sling to rest the shoulder. Patients may be given antiinflammatory medicine to help ease pain and swelling and to help return people to activity sooner after a biceps tendon rupture. These medications include common over-the-counter drugs such as ibuprofen.

Surgical treatment:

Surgery is reserved for patients who have pain that won't go away, severe loss of strength or are very concerned with the cosmetic appearance of the balled up biceps.

Biceps tenodesis is surgery to anchor the ruptured end of the biceps tendon to retension the muscle. There are many available techniques such as placing the end of the tendon into a hole drilled into the bone and fixing it with a screw, or suturing it to other tendons nearby.